Father Koch: Law finds its truest meaning in love

July 11, 2025 at 10:31 a.m.

Gospel reflection for July 13, 2025, 15th Sunday in Ordinary Time

As a general rule our relationship with laws are tenuous at best. Many of us easily ignore simple traffic laws, and pay whatever fines occur when we get caught violating one of them. We skirt around other ordinances, take liberty in reporting our taxes, and turn a blind eye to the many forms of injustice in our society. This does not necessarily make us bad citizens, evil people, or even recalcitrant sinners.

Nonetheless, the principle of law stands at the core of the establishment of good society. One of the criticisms of our Catholic faith, often by outsiders and certainly from some of us on the inside, is that we are focused on law, rules and regulations, and we miss pastoral opportunities and turn away more people than we welcome.

The establishment of religious law is not unique to Catholicism, having roots in our Jewish heritage, and in some parts of the world, even more ancient than that.

The function of religious law connects us first to right worship, and a proper disposition to the faith we profess. The Mosaic Law found in the Torah focused first on one’s responsibility to God, and then to one’s neighbor. This is seen in the Decalogue, but as we review the Laws – traditionally counted as 613 – this stands as the basis for all religious and social interaction.

Christians frequently disagree over the relationship that Jesus had with the Laws. At times Jesus seemed dismissive of the Law. He allowed his disciples to pick grain on the Sabbath and was accused of not following the law of ritual cleanliness. At the same time, he also states that not even a single diacritical mark of the written law would be abolished until the coming of the Kingdom of Heaven.

God not only gave the Law to the Israelites to form their identity as a theocratic society, but also to elevate that society among the other cultures of their time. While a twenty-first century reader of the Law sees them as archaic and often harsh, within their context, the opposite is always true. These laws tempered vengeance, and gave rise to a deeper sense of justice.

When Jesus is asked the question as to which is the greatest Law, he answers with the shemah, found in Deuteronomy chapter six. This is the great prayer of Judaism. He then expands his answer to include the love of neighbor.

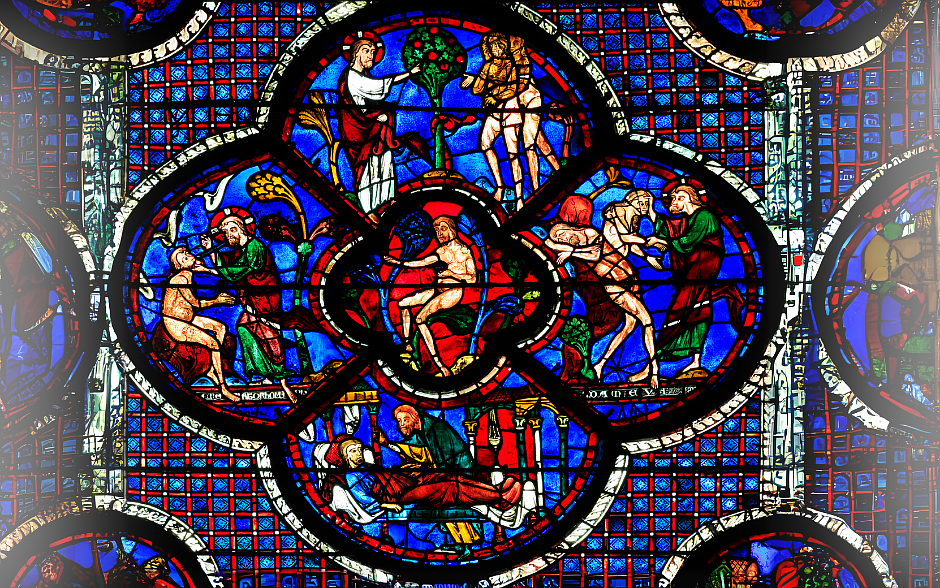

Further highlighting the point, and explaining in a real sense the meaning of Law, Jesus presents a parable that has become known as the parable of the Good Samaritan. The purpose of this parable is to emphasize the meaning of the Law which Jesus and the young scholar have been discussing.

What we learn is that law for the sake of law itself is meaningless. In the parable the priest and the Levite observed an aspect of the law, and in their own minds were correct in doing so. Many who were listening, including probably the scholar himself, understood that they did what the law required of them as they believed that the law of ritual purity superseded the law of love.

In the parable Jesus makes the exemplar of justice and love of neighbor a Samaritan. This was startling to the listeners, as Jews did not regard Samaritans with much esteem, although Samaritans like Jews followed the Law of Moses.

The Samaritan in the parable risks his own life in order to save the life of another; one who had their roles been reversed, may likely have not done the same for him. Why? Because the law of love and the law of justice demands it.

We live in this tension between law as regulation and restriction, and law as a means of exercising love and justice. While it is true that American civil law is less forgiving and more rigid than the understanding of Law in the Roman world and within the prescripts of Canon Law, we still have opportunities to exercise justice and mercy grounded in love as we both observe and enforce law.

We have ample opportunities in our daily lives to be observant of law, but the attitude with which we follow laws, regulations, and even exercise common decency and courtesy, should always first be grounded in love. To be aware of, considerate of, and compassionate to those around us – known and unknown – is the second commandment of love. The first commandment, of course, is love of God. As we love God we love our neighbor. If we do not love our neighbor, our love of God is hollow and not hallow.

Father Garry Koch is pastor of St. Benedict Parish, Holmdel.

Related Stories

Sunday, December 14, 2025

E-Editions

Events

Gospel reflection for July 13, 2025, 15th Sunday in Ordinary Time

As a general rule our relationship with laws are tenuous at best. Many of us easily ignore simple traffic laws, and pay whatever fines occur when we get caught violating one of them. We skirt around other ordinances, take liberty in reporting our taxes, and turn a blind eye to the many forms of injustice in our society. This does not necessarily make us bad citizens, evil people, or even recalcitrant sinners.

Nonetheless, the principle of law stands at the core of the establishment of good society. One of the criticisms of our Catholic faith, often by outsiders and certainly from some of us on the inside, is that we are focused on law, rules and regulations, and we miss pastoral opportunities and turn away more people than we welcome.

The establishment of religious law is not unique to Catholicism, having roots in our Jewish heritage, and in some parts of the world, even more ancient than that.

The function of religious law connects us first to right worship, and a proper disposition to the faith we profess. The Mosaic Law found in the Torah focused first on one’s responsibility to God, and then to one’s neighbor. This is seen in the Decalogue, but as we review the Laws – traditionally counted as 613 – this stands as the basis for all religious and social interaction.

Christians frequently disagree over the relationship that Jesus had with the Laws. At times Jesus seemed dismissive of the Law. He allowed his disciples to pick grain on the Sabbath and was accused of not following the law of ritual cleanliness. At the same time, he also states that not even a single diacritical mark of the written law would be abolished until the coming of the Kingdom of Heaven.

God not only gave the Law to the Israelites to form their identity as a theocratic society, but also to elevate that society among the other cultures of their time. While a twenty-first century reader of the Law sees them as archaic and often harsh, within their context, the opposite is always true. These laws tempered vengeance, and gave rise to a deeper sense of justice.

When Jesus is asked the question as to which is the greatest Law, he answers with the shemah, found in Deuteronomy chapter six. This is the great prayer of Judaism. He then expands his answer to include the love of neighbor.

Further highlighting the point, and explaining in a real sense the meaning of Law, Jesus presents a parable that has become known as the parable of the Good Samaritan. The purpose of this parable is to emphasize the meaning of the Law which Jesus and the young scholar have been discussing.

What we learn is that law for the sake of law itself is meaningless. In the parable the priest and the Levite observed an aspect of the law, and in their own minds were correct in doing so. Many who were listening, including probably the scholar himself, understood that they did what the law required of them as they believed that the law of ritual purity superseded the law of love.

In the parable Jesus makes the exemplar of justice and love of neighbor a Samaritan. This was startling to the listeners, as Jews did not regard Samaritans with much esteem, although Samaritans like Jews followed the Law of Moses.

The Samaritan in the parable risks his own life in order to save the life of another; one who had their roles been reversed, may likely have not done the same for him. Why? Because the law of love and the law of justice demands it.

We live in this tension between law as regulation and restriction, and law as a means of exercising love and justice. While it is true that American civil law is less forgiving and more rigid than the understanding of Law in the Roman world and within the prescripts of Canon Law, we still have opportunities to exercise justice and mercy grounded in love as we both observe and enforce law.

We have ample opportunities in our daily lives to be observant of law, but the attitude with which we follow laws, regulations, and even exercise common decency and courtesy, should always first be grounded in love. To be aware of, considerate of, and compassionate to those around us – known and unknown – is the second commandment of love. The first commandment, of course, is love of God. As we love God we love our neighbor. If we do not love our neighbor, our love of God is hollow and not hallow.

Father Garry Koch is pastor of St. Benedict Parish, Holmdel.