Benedictine estimates 70 million-plus pages of manuscripts digitized

October 10, 2019 at 8:40 p.m.

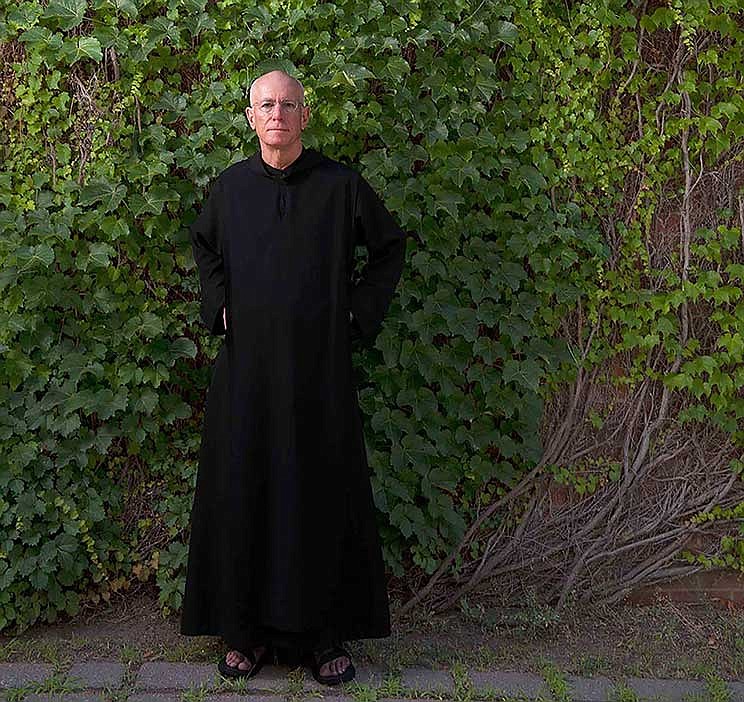

WASHINGTON – Benedictine Father Columba Stewart never imagined there would be 50 million pages of sacred manuscripts housed in the archives at the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library at St. John's College in Collegeville, Minnesota, where he has been since entering religious life in 1980.

He almost never had to.

"There were already 40 million when I started (in 2003). We've got to be closer to 60, 75 million," he said. Doing some quick calculations in his head, Father Stewart added, "I can tell you how many digital files: 12.5 million digital files post-2003, many of them are 20-page spreads. That suggests that our real number is closer to 70, 75 million."

It is doubtful that anyone entering Benedictine monastic life is identified from the get-go as having a charism in document preservation. Father Stewart is proof of it.

"Around 2002-2003, the library was getting some interest from Orthodox Christians in Lebanon to get some work in their manuscript heritage. I got drafted to be a sort of formal adviser on the project. I had traveled a bit, at least, and others had not. I could speak French, and that helped."

After that, he told Catholic News Service in an Oct. 8 phone interview, it was "just a series of factors – a leadership change at the library. I was asked to step in. I was asked to unlock the door on Monday after the doors had been locked on Friday. ... Sometimes these things happen, right?"

Father Stewart was in Washington to give the Jefferson Lecture presented by the National Endowment for the Humanities, which contributes funding for the library's work. He is away from St. John's Abbey about a quarter of the year, which could play havoc as far as keeping the rule of his monastic order.

"I pray the office. I actually have our own St. John's Liturgy of the Hours on my iPad," he said. "I use our 'Give Us This Day' monthly devotion, That's my companion. I do my meditation. And to stay sane, I never turn on the television in the hotel room, for example. That's my cardinal rule." This combination of prayer and practice, the priest added, gives him "the spiritual reflection I need as a monk and an introvert."

The digitization projects seem to have trouble – mostly civil war – break out not long after a project starts in a new country. "I just think it's a sign of the instability of the world, and you can't predict events like the Arab Spring, the rise of ISIS, which seems to come from nowhere – but it came from somewhere," Father Stewart said. ISIS, or now better known as IS, is the acronym for the Islamic State.

"Things blow up very suddenly. We happened to be on-site already, in both of those crises, having begun work, in Syria and Iraq, respectively, before their crises, even though it's grown more difficult to work" there because of the continuing violence, he added.

Despite the uncertainties posed by such conflict, both the projects and manuscripts have held up quite well, Father Stewart asserted. "The only manuscript collections we're certain were destroyed in the conflicts were in Mosul (Iraq), and we'd digitized most of that collection. We have manuscript collections in Syria and Iraq that have not been digitized, but they're safe," he said.

"What about the future? We don't have control over that."

Digitization projects are underway in 13 countries, and Father Stewart wants to add more to the list.

"We're very interested in Central Asia. We'd love to work in Afghanistan, but that's not really possible," he said. "There are other countries on the Silk Road connecting the Middle East to South Asia, and to China. It'd be great to connect with organizations along that route to see what they have. That'd be really fun to do. I don't know if that's going to happen, but we'll see."

The library relies greatly on local partners it can train to do the photography and digitization work. And despite the long-standing low numbers of vocations, Father Stewart said he does not think the library will suffer if no Benedictine can be found to replace him.

"I'm actually the only monk at St. John's directly involved with the library. We have a couple of monks on our board. We'll have monks working on and off. It's a kind of specialty work," he said.

"The day shall come when I'm no longer active. But this was started by monks at the abbey and inspired by the Benedictine charism," he added. "The monks are very proud of the work at the library. I think there will always be some kind of link."

Related Stories

Sunday, December 14, 2025

E-Editions

Events

WASHINGTON – Benedictine Father Columba Stewart never imagined there would be 50 million pages of sacred manuscripts housed in the archives at the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library at St. John's College in Collegeville, Minnesota, where he has been since entering religious life in 1980.

He almost never had to.

"There were already 40 million when I started (in 2003). We've got to be closer to 60, 75 million," he said. Doing some quick calculations in his head, Father Stewart added, "I can tell you how many digital files: 12.5 million digital files post-2003, many of them are 20-page spreads. That suggests that our real number is closer to 70, 75 million."

It is doubtful that anyone entering Benedictine monastic life is identified from the get-go as having a charism in document preservation. Father Stewart is proof of it.

"Around 2002-2003, the library was getting some interest from Orthodox Christians in Lebanon to get some work in their manuscript heritage. I got drafted to be a sort of formal adviser on the project. I had traveled a bit, at least, and others had not. I could speak French, and that helped."

After that, he told Catholic News Service in an Oct. 8 phone interview, it was "just a series of factors – a leadership change at the library. I was asked to step in. I was asked to unlock the door on Monday after the doors had been locked on Friday. ... Sometimes these things happen, right?"

Father Stewart was in Washington to give the Jefferson Lecture presented by the National Endowment for the Humanities, which contributes funding for the library's work. He is away from St. John's Abbey about a quarter of the year, which could play havoc as far as keeping the rule of his monastic order.

"I pray the office. I actually have our own St. John's Liturgy of the Hours on my iPad," he said. "I use our 'Give Us This Day' monthly devotion, That's my companion. I do my meditation. And to stay sane, I never turn on the television in the hotel room, for example. That's my cardinal rule." This combination of prayer and practice, the priest added, gives him "the spiritual reflection I need as a monk and an introvert."

The digitization projects seem to have trouble – mostly civil war – break out not long after a project starts in a new country. "I just think it's a sign of the instability of the world, and you can't predict events like the Arab Spring, the rise of ISIS, which seems to come from nowhere – but it came from somewhere," Father Stewart said. ISIS, or now better known as IS, is the acronym for the Islamic State.

"Things blow up very suddenly. We happened to be on-site already, in both of those crises, having begun work, in Syria and Iraq, respectively, before their crises, even though it's grown more difficult to work" there because of the continuing violence, he added.

Despite the uncertainties posed by such conflict, both the projects and manuscripts have held up quite well, Father Stewart asserted. "The only manuscript collections we're certain were destroyed in the conflicts were in Mosul (Iraq), and we'd digitized most of that collection. We have manuscript collections in Syria and Iraq that have not been digitized, but they're safe," he said.

"What about the future? We don't have control over that."

Digitization projects are underway in 13 countries, and Father Stewart wants to add more to the list.

"We're very interested in Central Asia. We'd love to work in Afghanistan, but that's not really possible," he said. "There are other countries on the Silk Road connecting the Middle East to South Asia, and to China. It'd be great to connect with organizations along that route to see what they have. That'd be really fun to do. I don't know if that's going to happen, but we'll see."

The library relies greatly on local partners it can train to do the photography and digitization work. And despite the long-standing low numbers of vocations, Father Stewart said he does not think the library will suffer if no Benedictine can be found to replace him.

"I'm actually the only monk at St. John's directly involved with the library. We have a couple of monks on our board. We'll have monks working on and off. It's a kind of specialty work," he said.

"The day shall come when I'm no longer active. But this was started by monks at the abbey and inspired by the Benedictine charism," he added. "The monks are very proud of the work at the library. I think there will always be some kind of link."