Discovering Dickens’ other Christmas tale

December 10, 2023 at 9:30 a.m.

Few pieces of English literature are more closely associated with Christmas than Charles Dickens’ novella, “A Christmas Carol.” For many people, the stage production or its many literal or analogous film adaptations are more familiar than the book. “A Christmas Carol” has provided characters and turns of phrase known even by people who scarcely know of the story. Scrooge and his exclamation “Bah! Humbug!” are common tropes even apart from the context of Christmas. Christmas ghost stories are perennial traditions for some families. And how many people have prayed “God bless as, every one!”, the last words of “A Christmas Carol,” uttered by Tiny Tim Cratchit?

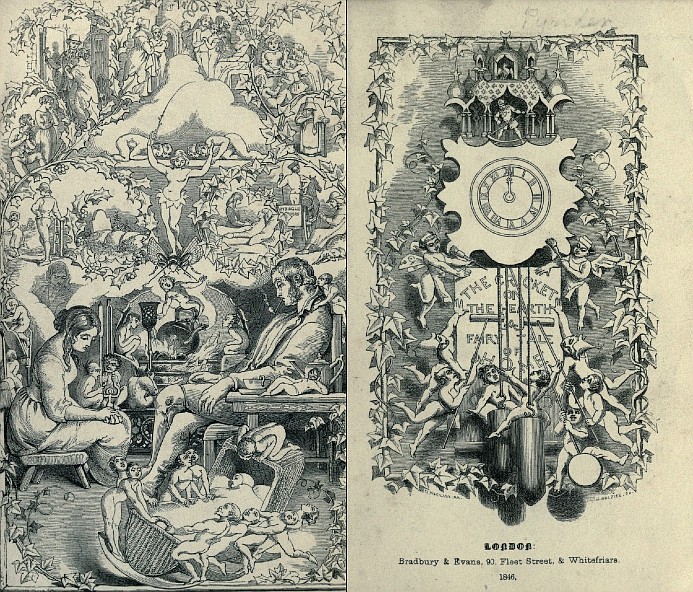

But “A Christmas Carol” is only the most prominent of Dickens’ several Christmas stories, my favorite of which is “The Cricket on the Hearth: A Fairy Tale of Home,” published on Dec. 20, 1845.

Other than by reference to the date of its publication, it may seem odd to call “Cricket” a Christmas story. It is set in late January. Christmas is never mentioned, and the story is devoid of explicit Christmas symbols or images. But the message of “The Cricket on the Hearth” places it squarely within any consideration of the spirit of Christmas. The fundamental themes of “Cricket” are selflessness, sacrificial giving, and disinterested gestures of love and grace. The journey to the conclusion is filled with hardship, bewilderment and disenchantment. And the narrative is constructed around an extravagant, mysterious surprise, carefully concealed and delightfully revealed.

Many characters in “The Cricket on the Hearth” have characteristics that are strikingly similar to those in “A Christmas Carol.” For example, big-hearted toymaker Caleb Plummer and his blind daughter, Bertha, are similar to Bob and Tim Cratchit. Caleb is employed by the mean, ill-tempered, Scrooge-like toyshop owner, Tackleton. John and Mary Peerybingle, at whose hearth the cricket chirps, are this story’s Mr. & Mrs. Fezziwig (although the Peerybingles are more central to “Cricket” than are the Fezziwigs to “Carol”).

Unsurprisingly, the dynamic relationships among these characters are analogous to the interactions in “A Christmas Carol.” And I am giving nothing of the story away to say that its ending is satisfying and joyous. It is, after all, a Christmas story.

The cricket from “The Cricket on the Hearth” is both an insect in the Peerybingle’s living room and metaphor for John and Mary’s hospitality and generosity. Along with the teapot, it supplies the chorus for the comedic dialogue and narrative of the tale.

The cricket makes the Peerybingle’s house more than “four walls and a ceiling.” It’s the symbol of a hospitable and welcoming home. When the cricket stops chirping, “somehow the room was not so cheerful as it had been. Nothing like it.” For the Peerybingles, it is a comforting companion; for Tackleton a noisome nuisance. Tackleton: “Why don’t you kill that Cricket?” John: “You kill your Crickets, eh?” Tackleton: “Scrunch ’em, sir.”

Thus is Tackleton’s bleak house, by his own description, nothing more than “four walls and a ceiling.”

Part of the contentment of reading “The Cricket on the Hearth” is the felicity of Dickens’s prose. For example, after Mrs. Peerybingle fills the tea kettle in the outdoor fountain on a cold January evening, she sets the kettle on the fire. “In doing which she lost her temper, or mislaid it for an instant; for the water, being uncomfortably cold, and in that slippery, slushy, sleety sort of state wherein it seems to penetrate through every kind of substance . . . had laid hold of Mrs. Peerybingle’s toes.”

Similarly, Dickens’s anthropomorphisms are a continuous delight. The kettle “wouldn’t hear of accommodating itself kindly to the knobs of coal,” for example. It “WOULD lean forward with a drunken air, and dribble … on the hearth. It was quarrelsome, and hissed and spluttered morosely at the fire.” The “sullen and pig-headed” kettle was defiant, “cocking its spout pertly and mockingly at Mrs. Peerybingle, as if it said, ‘I won’t boil. Nothing shall induce me!’”

Delightful to the ear and eye as these and many other passages are, however, the virtue of its characters and the power of its narrative are what make “The Cricket on the Hearth” such a delightful tale. The story radiates the light of Christian charity, echoing themes of generosity and joy, focusing the luminosity of God’s gift to man in the unique event of the Incarnation. God’s grace came to us through a Man and he calls us participatively to share that grace with one another. If that is the message of Christmas, “The Cricket on the Hearth” is a complete Christmas story.

Kenneth Craycraft is an associate professor of moral theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary and School of Theology in Cincinnati.

Related Stories

Monday, December 15, 2025

E-Editions

Events

Few pieces of English literature are more closely associated with Christmas than Charles Dickens’ novella, “A Christmas Carol.” For many people, the stage production or its many literal or analogous film adaptations are more familiar than the book. “A Christmas Carol” has provided characters and turns of phrase known even by people who scarcely know of the story. Scrooge and his exclamation “Bah! Humbug!” are common tropes even apart from the context of Christmas. Christmas ghost stories are perennial traditions for some families. And how many people have prayed “God bless as, every one!”, the last words of “A Christmas Carol,” uttered by Tiny Tim Cratchit?

But “A Christmas Carol” is only the most prominent of Dickens’ several Christmas stories, my favorite of which is “The Cricket on the Hearth: A Fairy Tale of Home,” published on Dec. 20, 1845.

Other than by reference to the date of its publication, it may seem odd to call “Cricket” a Christmas story. It is set in late January. Christmas is never mentioned, and the story is devoid of explicit Christmas symbols or images. But the message of “The Cricket on the Hearth” places it squarely within any consideration of the spirit of Christmas. The fundamental themes of “Cricket” are selflessness, sacrificial giving, and disinterested gestures of love and grace. The journey to the conclusion is filled with hardship, bewilderment and disenchantment. And the narrative is constructed around an extravagant, mysterious surprise, carefully concealed and delightfully revealed.

Many characters in “The Cricket on the Hearth” have characteristics that are strikingly similar to those in “A Christmas Carol.” For example, big-hearted toymaker Caleb Plummer and his blind daughter, Bertha, are similar to Bob and Tim Cratchit. Caleb is employed by the mean, ill-tempered, Scrooge-like toyshop owner, Tackleton. John and Mary Peerybingle, at whose hearth the cricket chirps, are this story’s Mr. & Mrs. Fezziwig (although the Peerybingles are more central to “Cricket” than are the Fezziwigs to “Carol”).

Unsurprisingly, the dynamic relationships among these characters are analogous to the interactions in “A Christmas Carol.” And I am giving nothing of the story away to say that its ending is satisfying and joyous. It is, after all, a Christmas story.

The cricket from “The Cricket on the Hearth” is both an insect in the Peerybingle’s living room and metaphor for John and Mary’s hospitality and generosity. Along with the teapot, it supplies the chorus for the comedic dialogue and narrative of the tale.

The cricket makes the Peerybingle’s house more than “four walls and a ceiling.” It’s the symbol of a hospitable and welcoming home. When the cricket stops chirping, “somehow the room was not so cheerful as it had been. Nothing like it.” For the Peerybingles, it is a comforting companion; for Tackleton a noisome nuisance. Tackleton: “Why don’t you kill that Cricket?” John: “You kill your Crickets, eh?” Tackleton: “Scrunch ’em, sir.”

Thus is Tackleton’s bleak house, by his own description, nothing more than “four walls and a ceiling.”

Part of the contentment of reading “The Cricket on the Hearth” is the felicity of Dickens’s prose. For example, after Mrs. Peerybingle fills the tea kettle in the outdoor fountain on a cold January evening, she sets the kettle on the fire. “In doing which she lost her temper, or mislaid it for an instant; for the water, being uncomfortably cold, and in that slippery, slushy, sleety sort of state wherein it seems to penetrate through every kind of substance . . . had laid hold of Mrs. Peerybingle’s toes.”

Similarly, Dickens’s anthropomorphisms are a continuous delight. The kettle “wouldn’t hear of accommodating itself kindly to the knobs of coal,” for example. It “WOULD lean forward with a drunken air, and dribble … on the hearth. It was quarrelsome, and hissed and spluttered morosely at the fire.” The “sullen and pig-headed” kettle was defiant, “cocking its spout pertly and mockingly at Mrs. Peerybingle, as if it said, ‘I won’t boil. Nothing shall induce me!’”

Delightful to the ear and eye as these and many other passages are, however, the virtue of its characters and the power of its narrative are what make “The Cricket on the Hearth” such a delightful tale. The story radiates the light of Christian charity, echoing themes of generosity and joy, focusing the luminosity of God’s gift to man in the unique event of the Incarnation. God’s grace came to us through a Man and he calls us participatively to share that grace with one another. If that is the message of Christmas, “The Cricket on the Hearth” is a complete Christmas story.

Kenneth Craycraft is an associate professor of moral theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary and School of Theology in Cincinnati.