FAITH ALIVE: 'Development means peace,' 1967 encyclical said

July 29, 2019 at 12:37 p.m.

By David Gibson | Catholic News Service

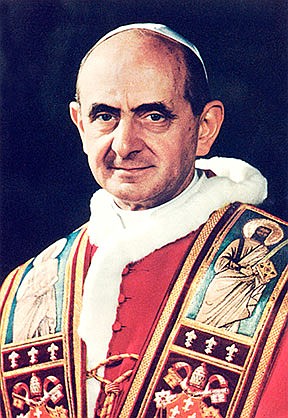

Development is "the new name for peace," Blessed Paul VI declared in "The Progress of Peoples" ("Populorum Progressio"). Those well-known words reflect the heart and soul of this encyclical, whose 50th anniversary we celebrate in 2017.

Blessed Paul wanted to communicate a clear message that "peace is not simply the absence of warfare, based on a precarious balance of power." Extreme economic, social and educational disparities between nations often jeopardize peace between them, he stressed.

It is essential, moreover, to promote human development in integral forms -- forms that not only "fight poverty and oppose the unfair conditions of the present" but that promote "spiritual and moral development" in human lives and, as a result, benefit "the whole human race."

He cherished a hope "that distrust and selfishness among nations will eventually be overcome by a stronger desire for mutual collaboration and a heightened sense of solidarity."

The encyclical concluded on a uniquely optimistic and assured note that, at once, encompassed a blunt challenge. He wrote:

"Knowing, as we all do, that development means peace these days, what man would not want to work for it with every ounce of his strength? No one, of course."

Might those confident words penned in 1967 leave some in today's globalized world shaking their heads -- asking, perhaps, what development implies in a world where a fear of "others" has grown so familiar?

The encyclical's publication came a little more than two years after the Second Vatican Council's conclusion. It was Blessed Paul who presided over the council's final stages -- the time, notably, when it completed its Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World ("Gaudium et Spes"). He promulgated that council document Dec. 7, 1965.

"Christians, on pilgrimage toward the heavenly city," the pastoral constitution acknowledged, "should seek and think" of the things that "are above." Yet, it added, "this duty in no way decreases, rather it increases, the importance of their obligation to work with all men in the building of a more human world."

It would be hard to exaggerate the interest many Catholics took during the latter part of the 1960s in issues of international social justice and the deprivations afflicting the world's poor. Countless believers welcomed the opportunity to discover how to connect worship and prayer with the world's concrete needs.

University students, for example, crowded into lecture halls to hear Barbara Ward, an influential and widely known British Catholic economist and writer, explain the demands of justice and the harsh realities of injustice.

When Ward died in 1981, The New York Times called her "an eloquent evangelist for the needs of the developing countries and for the interdependence of nations."

When she addressed the October 1971 world Synod of Bishops in Rome, one of whose two themes was "Justice in the World," she pointed out to church leaders from around the world that a "fundamental maldistribution of the world's resources" was a key concern "against which Pope Paul raised his powerful protest" in "The Progress of Peoples."

Pope Benedict XVI paid tribute to "The Progress of Peoples" in his 2009 encyclical titled "Charity in Truth" ("Caritas in Veritate"). His conviction was, Pope Benedict said, that Blessed Paul's encyclical ought to be considered "the 'Rerum Novarum' of the present age."

That is high praise, since "Rerum Novarum," Pope Leo XIII's 1891 encyclical on the rights of capital and labor in a time of "revolutionary change," is esteemed for creating Catholic social teaching's foundation in modern times.

To suggest that "The Progress of Peoples" played a similar role 76 years later appears to suggest that it signaled the arrival of a new era in Catholic social teaching.

Pope Benedict said that "Paul VI, like Leo XIII before him in 'Rerum Novarum,' knew that he was carrying out a duty proper to his office by shedding the light of the Gospel on the social questions of his time."

Moreover, he "grasped the interconnection between the impetus toward the unification of humanity and the Christian ideal of a single family of peoples in solidarity and fraternity."

It is said that the more things change, the more they stay the same. There is truth in this. Certainly, some of Blessed Paul's 1967 words read almost as if intended to address 21st-century issues.

A spirit of nationalism has arisen within numerous nations today, and nationalism ranked among Blessed Paul's concerns 50 years ago. He cautioned that "haughty pride in one's own nation disunites nations and poses obstacles to their true welfare."

It is commendable, he commented, to prize the cultural tradition of one's nation. Yet, "this commendable attitude should be further ennobled by love, a love for the whole family of man."

"The Progress of Peoples" observed that "human society is sorely ill." However, it said, "the cause is not so much the depletion of natural resources, nor their monopolistic control by a privileged few; it is rather the weakening of brotherly ties between individuals and nations."

Gibson served on Catholic News Service's editorial staff for 37 years.

Living justly in a changing world

By Daniel Mulhall | Catholic News Service

On March 26, 1967, Blessed Paul VI promulgated his social encyclical "Populorum Progressio" ("The Progress of Peoples").

In doing this, Blessed Paul continued in the footsteps of his predecessors Pope Leo XIII, Pope Pius XI and St. John XXIII in enunciating the church's social teaching and how it was to be implemented throughout in the world.

Just as Pope Leo XIII had done in 1891 when he focused his encyclical "Rerum Novarum" on the changes happening in the world between workers and business owners, Blessed Paul focused his attention on the changes happening at the end of colonialism and the spread of industrialization.

He offered guidance to countries as they implemented their newly found freedom, suggesting a path they could follow to set up a nation built on justice. The encyclical also proposed what others could do to assist these new nations as they came into being, so that all the countries' people would benefit, not just the rich or the well-connected.

Pope Paul begins the encyclical with these words:

"The progressive development of peoples is an object of deep interest and concern to the church. This is particularly true in the case of those peoples who are trying to escape the ravages of hunger, poverty, endemic disease and ignorance; of those who are seeking a larger share in the benefits of civilization and a more active improvement of their human qualities; of those who are consciously striving for fuller growth."

From the middle of the 1400s, explorers from Portugal began their voyages around the southern tip of Africa (Cape Hope) seeking to participate in the Asian trade market for silk and spices. European nations grew wealthy from the colonies they established in Africa, Asia and the Americas.

While some colonies, such as the United States of America, Mexico and Brazil, won their independence in the 18th and 19th centuries, others, especially those in Africa and Asia, didn't gain their independence until the 1950s and 1960s.

Although colonization did, at times, benefit the colony -- Britain created an effective rail system in India and gave it a common language with English -- the overall effects of colonization were not beneficial to most of the people who lived there.

Great amounts of wealth were extracted from the colonies, but very little wealth was reinvested in them and only a few people in the colonies benefited. The results of this were that most of the people remained in poverty, were limited in the amount of education they could receive and were subjugated by the colonizers.

When these colonies won or were given their freedom following World War II, they were left with systems that were not healthy or sustainable over the long term.

As Blessed Paul wrote, "It is true that colonizing nations were sometimes concerned with nothing save their own interests, their own power and their own prestige; their departure left the economy of these countries in precarious imbalance -- the one-crop economy, for example, that is at the mercy of sudden, wide-ranging fluctuations in market prices. Certain types of colonialism surely caused harm and paved the way for further troubles."

The encyclical also addressed the dramatic changes that were happening throughout the world because of upended social and religious cultural practices brought about by the destruction of World War II, the "social unrest" caused by rapid industrialization and the destruction of subsistence farming and the "flagrant inequalities" in countries where the rich grew richer at the suffering of the poor.

Blessed Paul also spoke of the problem of rich nations and companies within those nations continuing to take advantage of the poor.

Fifty years later, people still suffer from the same ills that Blessed Paul addressed. His solution to these ills and his call for all people to work for justice is just as needed today as it was in 1967.

Mulhall is a catechist who lives in Louisville, Kentucky.

Fifty years after 'Populorum Progressio'

By Father Graham Golden, OPraem | Catholic News Service

As our nation saw the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the emergence of the War on Poverty, the Catholic Church saw the advent of a landmark expression of its own social doctrine when Blessed Paul VI promulgated "Populorum Progressio" ("The Progress of Peoples") in 1967 as the first concrete application of the Second Vatican Council's Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World ("Gaudium et Spes").

The challenges that faced the world half a century ago still press upon us. We see contentious debate over the value of nationalism, the significance of borders, tensions between globalization and isolation, divisions between rich and poor, racial violence and uncertainty over the future of health care and social safety nets. So too has the church's response to these issues endured.

"Populorum Progressio" has found contemporary expression in "Laudato Si'," "Evangelii Gaudium" and was the central foundation for Pope Benedict XVI's response to the global economic crisis of 2008 in "Caritas in Veritate."

What Blessed Paul expressed is an understanding of the human person that is inherently relational, mutually responsible and developmental. Human activity and social policy should be rooted in our capacity to grow, and we should grow together and with God.

This process of integral human development considers not only economics, but a comprehensive understanding of human flourishing, including "the higher values of love and friendship, of prayer and contemplation."

This development expresses the value of our activity as a means to seek the dignity to which we are called by God as "artisans of destiny."

It is a perspective that neither upholds or condemns institutions or programs, but calls all human activity (economic, social, public, private, technological and cultural) to have its primary end as the well-being of the common good of all peoples, and even more so an eternal goal.

The whole only finds its purpose when engaged in promoting the good of the individual, and the individual when they are seeking to contribute to the whole. This is true at every level from within communities to between nations.

Blessed Paul recognized that his call for mutual solidarity, social justice and universal charity was directed toward a deeper brokenness within our own self-understanding:

"Human society is sorely ill. The cause is not so much the depletion of natural resources, nor their monopolistic control by a privileged few; it is rather the weakening of brotherly ties between individuals and nations."

"Populorum Progressio" asserts that our attempts to solve the social challenges of our time -- from mass migration to health care -- will never be successful until we understand the relationality that defines our identity and value as more than something quantifiable.

Until solidarity, human flourishing and universal dignity in God become the benchmarks by which we direct human enterprise, no human ills will find their resolution.

In the wake of the fear, hatred, division and uncertainty that still plague our world 50 years later, the words of Blessed Paul may be more pertinent than ever.

Father Golden, a Nobertine priest, writes from New Mexico. He is the winner of the Catholic Campaign for Human Development's 2016 Cardinal Bernardin New Leadership Award.

Enduring themes of 'Populorum Progressio'

By Jill Rauh | Catholic News Service

In Washington, DC, students at Gonzaga College High School learn practical skills to become nonviolent peacemakers. In Portland, the archdiocese trains clergy to seek economic justice for workers. Near Miami, St. Thomas University supports economic development in Haiti through a fair trade cooperative. And in the Archdiocese of San Antonio, youth act in solidarity with communities that lack access to water.

On the 50th anniversary of Blessed Paul VI's encyclical, "Populorum Progressio" ("The Progress of Peoples"), these are just a few examples from WeAreSaltAndLight.org of how faith communities are responding to Blessed Paul's call today.

Blessed Paul spent the first years of his pontificate shepherding the Second Vatican Council to its conclusion, visiting the United States and the Holy Land.

In doing so, he brought the Catholic Church into the modern world, began healing ancient divisions among Christians and challenged the entire world to peace. His 1967 contribution to the church's social tradition, "Populorum Progressio," has been called the "Magna Carta on development."

In it, Blessed Paul builds on the rich social teaching of Pope Leo XIII, Pope Pius XI and St. John XXIII, and focuses on inequality and underdevelopment. He offers a global vision for economic justice, development and solidarity. This vision is as challenging now as it was 50 years ago.

Here are a few major themes of enduring relevance:

-- Ending poverty: a mandate for all.

Blessed Paul writes: "The hungry nations of the world cry out to the peoples blessed with abundance. And the church, cut to the quick by this cry, asks each and every man to hear his brother's plea and answer it lovingly." Ending poverty is the responsibility of all of us.

-- Economic justice.

We must work toward a world where all people can be "artisans of their destiny" and where "Lazarus can sit down with the rich man at the same banquet table." The economy must serve the human person (not the other way around).

We must address inequality, restore dignity to workers and remember that the needs and rights of those in poverty take precedence over the rights of individuals to amass great wealth. The church has a preferential option for the poor.

-- "Development, the new name for peace."

War, which destroys societies and communities, and which Blessed Paul railed against in his 1965 address to the United Nations, is human development in reverse. "Peace is not simply the absence of warfare."

Authentic development responds to the needs of the whole person, including both material and spiritual, and results from fighting poverty and establishing justice. Blessed Paul would distill this in his World Day of Peace 1972 message: "If you want peace, work for justice."

-- Solidarity.

True development requires a commitment to solidarity -- the idea that we are one human family, each responsible for all. Without solidarity, there can be no progress toward complete development.

Those who are wealthy can also be poor, as they live blinded by selfishness. We have to overcome our isolation from others, so that "the glow of brotherly love and the helping hand of God" is reflected in all our relationships and decisions.

-- Think global, act local.

Inequality is a global issue. Wealthy countries should help poor nations through aid, relief for countries "overwhelmed by debts," equitable "trade relations," "hospitable reception" for immigrants, and, for businesses operating overseas, a focus on "social progress" instead of "self-interest."

So enduring was Blessed Paul's vision, St. John Paul II revisited it in "Sollicitudo Rei Socialis" in 1987, as did Pope Benedict XVI in "Caritas in Veritate" in 2009. Its themes are also strongly apparent in Pope Francis' vision of peace rooted in integral human development in "Evangelii Gaudium" and "Laudato Si'."

Blessed Paul and Pope Francis both challenge our current response to poverty and violence. They challenge us with the alternative of a vision that is cohesive and global, Catholic in the truest sense.

Rauh is the assistant director for education and outreach within the Catholic Campaign for Human Development at the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. A longer version of this article appears on the USCCB Department of Justice, Peace and Human Development's blog, togoforth.org.

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

Oct. 4, 1965, about a year and a half before promulgating his social encyclical "Populorum Progressio," Blessed Paul VI addressed the United Nations on its 20th anniversary. His speech highlighted themes that would later appear in his encyclical.

The U.N., Blessed Paul said, is accomplishing a great work: "teaching men peace." Peace "is not built merely by means of politics and a balance of power and interests" but "is built with the mind, with ideas, with the works of peace," the pope continued.

Blessed Paul named disarmament as one pathway toward peace: "If you want to be brothers, let the arms fall from your hands."

The pope also reminded the U.N. that "the edifice you are building does not rest on purely material and terrestrial foundations" but "upon consciences." In an age "marked by such great human progress," he said, "the appeal to the moral conscience of man has never before been as necessary."

Neither progress itself or science pose direct dangers, but can be used for good, he said. But "the real danger comes from man, who has at his disposal ever more powerful instruments." Modern civilization, concluded Blessed Paul, must be built from spiritual principles.

[[In-content Ad]]Related Stories

Saturday, July 27, 2024

E-Editions

Events

By David Gibson | Catholic News Service

Development is "the new name for peace," Blessed Paul VI declared in "The Progress of Peoples" ("Populorum Progressio"). Those well-known words reflect the heart and soul of this encyclical, whose 50th anniversary we celebrate in 2017.

Blessed Paul wanted to communicate a clear message that "peace is not simply the absence of warfare, based on a precarious balance of power." Extreme economic, social and educational disparities between nations often jeopardize peace between them, he stressed.

It is essential, moreover, to promote human development in integral forms -- forms that not only "fight poverty and oppose the unfair conditions of the present" but that promote "spiritual and moral development" in human lives and, as a result, benefit "the whole human race."

He cherished a hope "that distrust and selfishness among nations will eventually be overcome by a stronger desire for mutual collaboration and a heightened sense of solidarity."

The encyclical concluded on a uniquely optimistic and assured note that, at once, encompassed a blunt challenge. He wrote:

"Knowing, as we all do, that development means peace these days, what man would not want to work for it with every ounce of his strength? No one, of course."

Might those confident words penned in 1967 leave some in today's globalized world shaking their heads -- asking, perhaps, what development implies in a world where a fear of "others" has grown so familiar?

The encyclical's publication came a little more than two years after the Second Vatican Council's conclusion. It was Blessed Paul who presided over the council's final stages -- the time, notably, when it completed its Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World ("Gaudium et Spes"). He promulgated that council document Dec. 7, 1965.

"Christians, on pilgrimage toward the heavenly city," the pastoral constitution acknowledged, "should seek and think" of the things that "are above." Yet, it added, "this duty in no way decreases, rather it increases, the importance of their obligation to work with all men in the building of a more human world."

It would be hard to exaggerate the interest many Catholics took during the latter part of the 1960s in issues of international social justice and the deprivations afflicting the world's poor. Countless believers welcomed the opportunity to discover how to connect worship and prayer with the world's concrete needs.

University students, for example, crowded into lecture halls to hear Barbara Ward, an influential and widely known British Catholic economist and writer, explain the demands of justice and the harsh realities of injustice.

When Ward died in 1981, The New York Times called her "an eloquent evangelist for the needs of the developing countries and for the interdependence of nations."

When she addressed the October 1971 world Synod of Bishops in Rome, one of whose two themes was "Justice in the World," she pointed out to church leaders from around the world that a "fundamental maldistribution of the world's resources" was a key concern "against which Pope Paul raised his powerful protest" in "The Progress of Peoples."

Pope Benedict XVI paid tribute to "The Progress of Peoples" in his 2009 encyclical titled "Charity in Truth" ("Caritas in Veritate"). His conviction was, Pope Benedict said, that Blessed Paul's encyclical ought to be considered "the 'Rerum Novarum' of the present age."

That is high praise, since "Rerum Novarum," Pope Leo XIII's 1891 encyclical on the rights of capital and labor in a time of "revolutionary change," is esteemed for creating Catholic social teaching's foundation in modern times.

To suggest that "The Progress of Peoples" played a similar role 76 years later appears to suggest that it signaled the arrival of a new era in Catholic social teaching.

Pope Benedict said that "Paul VI, like Leo XIII before him in 'Rerum Novarum,' knew that he was carrying out a duty proper to his office by shedding the light of the Gospel on the social questions of his time."

Moreover, he "grasped the interconnection between the impetus toward the unification of humanity and the Christian ideal of a single family of peoples in solidarity and fraternity."

It is said that the more things change, the more they stay the same. There is truth in this. Certainly, some of Blessed Paul's 1967 words read almost as if intended to address 21st-century issues.

A spirit of nationalism has arisen within numerous nations today, and nationalism ranked among Blessed Paul's concerns 50 years ago. He cautioned that "haughty pride in one's own nation disunites nations and poses obstacles to their true welfare."

It is commendable, he commented, to prize the cultural tradition of one's nation. Yet, "this commendable attitude should be further ennobled by love, a love for the whole family of man."

"The Progress of Peoples" observed that "human society is sorely ill." However, it said, "the cause is not so much the depletion of natural resources, nor their monopolistic control by a privileged few; it is rather the weakening of brotherly ties between individuals and nations."

Gibson served on Catholic News Service's editorial staff for 37 years.

Living justly in a changing world

By Daniel Mulhall | Catholic News Service

On March 26, 1967, Blessed Paul VI promulgated his social encyclical "Populorum Progressio" ("The Progress of Peoples").

In doing this, Blessed Paul continued in the footsteps of his predecessors Pope Leo XIII, Pope Pius XI and St. John XXIII in enunciating the church's social teaching and how it was to be implemented throughout in the world.

Just as Pope Leo XIII had done in 1891 when he focused his encyclical "Rerum Novarum" on the changes happening in the world between workers and business owners, Blessed Paul focused his attention on the changes happening at the end of colonialism and the spread of industrialization.

He offered guidance to countries as they implemented their newly found freedom, suggesting a path they could follow to set up a nation built on justice. The encyclical also proposed what others could do to assist these new nations as they came into being, so that all the countries' people would benefit, not just the rich or the well-connected.

Pope Paul begins the encyclical with these words:

"The progressive development of peoples is an object of deep interest and concern to the church. This is particularly true in the case of those peoples who are trying to escape the ravages of hunger, poverty, endemic disease and ignorance; of those who are seeking a larger share in the benefits of civilization and a more active improvement of their human qualities; of those who are consciously striving for fuller growth."

From the middle of the 1400s, explorers from Portugal began their voyages around the southern tip of Africa (Cape Hope) seeking to participate in the Asian trade market for silk and spices. European nations grew wealthy from the colonies they established in Africa, Asia and the Americas.

While some colonies, such as the United States of America, Mexico and Brazil, won their independence in the 18th and 19th centuries, others, especially those in Africa and Asia, didn't gain their independence until the 1950s and 1960s.

Although colonization did, at times, benefit the colony -- Britain created an effective rail system in India and gave it a common language with English -- the overall effects of colonization were not beneficial to most of the people who lived there.

Great amounts of wealth were extracted from the colonies, but very little wealth was reinvested in them and only a few people in the colonies benefited. The results of this were that most of the people remained in poverty, were limited in the amount of education they could receive and were subjugated by the colonizers.

When these colonies won or were given their freedom following World War II, they were left with systems that were not healthy or sustainable over the long term.

As Blessed Paul wrote, "It is true that colonizing nations were sometimes concerned with nothing save their own interests, their own power and their own prestige; their departure left the economy of these countries in precarious imbalance -- the one-crop economy, for example, that is at the mercy of sudden, wide-ranging fluctuations in market prices. Certain types of colonialism surely caused harm and paved the way for further troubles."

The encyclical also addressed the dramatic changes that were happening throughout the world because of upended social and religious cultural practices brought about by the destruction of World War II, the "social unrest" caused by rapid industrialization and the destruction of subsistence farming and the "flagrant inequalities" in countries where the rich grew richer at the suffering of the poor.

Blessed Paul also spoke of the problem of rich nations and companies within those nations continuing to take advantage of the poor.

Fifty years later, people still suffer from the same ills that Blessed Paul addressed. His solution to these ills and his call for all people to work for justice is just as needed today as it was in 1967.

Mulhall is a catechist who lives in Louisville, Kentucky.

Fifty years after 'Populorum Progressio'

By Father Graham Golden, OPraem | Catholic News Service

As our nation saw the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the emergence of the War on Poverty, the Catholic Church saw the advent of a landmark expression of its own social doctrine when Blessed Paul VI promulgated "Populorum Progressio" ("The Progress of Peoples") in 1967 as the first concrete application of the Second Vatican Council's Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World ("Gaudium et Spes").

The challenges that faced the world half a century ago still press upon us. We see contentious debate over the value of nationalism, the significance of borders, tensions between globalization and isolation, divisions between rich and poor, racial violence and uncertainty over the future of health care and social safety nets. So too has the church's response to these issues endured.

"Populorum Progressio" has found contemporary expression in "Laudato Si'," "Evangelii Gaudium" and was the central foundation for Pope Benedict XVI's response to the global economic crisis of 2008 in "Caritas in Veritate."

What Blessed Paul expressed is an understanding of the human person that is inherently relational, mutually responsible and developmental. Human activity and social policy should be rooted in our capacity to grow, and we should grow together and with God.

This process of integral human development considers not only economics, but a comprehensive understanding of human flourishing, including "the higher values of love and friendship, of prayer and contemplation."

This development expresses the value of our activity as a means to seek the dignity to which we are called by God as "artisans of destiny."

It is a perspective that neither upholds or condemns institutions or programs, but calls all human activity (economic, social, public, private, technological and cultural) to have its primary end as the well-being of the common good of all peoples, and even more so an eternal goal.

The whole only finds its purpose when engaged in promoting the good of the individual, and the individual when they are seeking to contribute to the whole. This is true at every level from within communities to between nations.

Blessed Paul recognized that his call for mutual solidarity, social justice and universal charity was directed toward a deeper brokenness within our own self-understanding:

"Human society is sorely ill. The cause is not so much the depletion of natural resources, nor their monopolistic control by a privileged few; it is rather the weakening of brotherly ties between individuals and nations."

"Populorum Progressio" asserts that our attempts to solve the social challenges of our time -- from mass migration to health care -- will never be successful until we understand the relationality that defines our identity and value as more than something quantifiable.

Until solidarity, human flourishing and universal dignity in God become the benchmarks by which we direct human enterprise, no human ills will find their resolution.

In the wake of the fear, hatred, division and uncertainty that still plague our world 50 years later, the words of Blessed Paul may be more pertinent than ever.

Father Golden, a Nobertine priest, writes from New Mexico. He is the winner of the Catholic Campaign for Human Development's 2016 Cardinal Bernardin New Leadership Award.

Enduring themes of 'Populorum Progressio'

By Jill Rauh | Catholic News Service

In Washington, DC, students at Gonzaga College High School learn practical skills to become nonviolent peacemakers. In Portland, the archdiocese trains clergy to seek economic justice for workers. Near Miami, St. Thomas University supports economic development in Haiti through a fair trade cooperative. And in the Archdiocese of San Antonio, youth act in solidarity with communities that lack access to water.

On the 50th anniversary of Blessed Paul VI's encyclical, "Populorum Progressio" ("The Progress of Peoples"), these are just a few examples from WeAreSaltAndLight.org of how faith communities are responding to Blessed Paul's call today.

Blessed Paul spent the first years of his pontificate shepherding the Second Vatican Council to its conclusion, visiting the United States and the Holy Land.

In doing so, he brought the Catholic Church into the modern world, began healing ancient divisions among Christians and challenged the entire world to peace. His 1967 contribution to the church's social tradition, "Populorum Progressio," has been called the "Magna Carta on development."

In it, Blessed Paul builds on the rich social teaching of Pope Leo XIII, Pope Pius XI and St. John XXIII, and focuses on inequality and underdevelopment. He offers a global vision for economic justice, development and solidarity. This vision is as challenging now as it was 50 years ago.

Here are a few major themes of enduring relevance:

-- Ending poverty: a mandate for all.

Blessed Paul writes: "The hungry nations of the world cry out to the peoples blessed with abundance. And the church, cut to the quick by this cry, asks each and every man to hear his brother's plea and answer it lovingly." Ending poverty is the responsibility of all of us.

-- Economic justice.

We must work toward a world where all people can be "artisans of their destiny" and where "Lazarus can sit down with the rich man at the same banquet table." The economy must serve the human person (not the other way around).

We must address inequality, restore dignity to workers and remember that the needs and rights of those in poverty take precedence over the rights of individuals to amass great wealth. The church has a preferential option for the poor.

-- "Development, the new name for peace."

War, which destroys societies and communities, and which Blessed Paul railed against in his 1965 address to the United Nations, is human development in reverse. "Peace is not simply the absence of warfare."

Authentic development responds to the needs of the whole person, including both material and spiritual, and results from fighting poverty and establishing justice. Blessed Paul would distill this in his World Day of Peace 1972 message: "If you want peace, work for justice."

-- Solidarity.

True development requires a commitment to solidarity -- the idea that we are one human family, each responsible for all. Without solidarity, there can be no progress toward complete development.

Those who are wealthy can also be poor, as they live blinded by selfishness. We have to overcome our isolation from others, so that "the glow of brotherly love and the helping hand of God" is reflected in all our relationships and decisions.

-- Think global, act local.

Inequality is a global issue. Wealthy countries should help poor nations through aid, relief for countries "overwhelmed by debts," equitable "trade relations," "hospitable reception" for immigrants, and, for businesses operating overseas, a focus on "social progress" instead of "self-interest."

So enduring was Blessed Paul's vision, St. John Paul II revisited it in "Sollicitudo Rei Socialis" in 1987, as did Pope Benedict XVI in "Caritas in Veritate" in 2009. Its themes are also strongly apparent in Pope Francis' vision of peace rooted in integral human development in "Evangelii Gaudium" and "Laudato Si'."

Blessed Paul and Pope Francis both challenge our current response to poverty and violence. They challenge us with the alternative of a vision that is cohesive and global, Catholic in the truest sense.

Rauh is the assistant director for education and outreach within the Catholic Campaign for Human Development at the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. A longer version of this article appears on the USCCB Department of Justice, Peace and Human Development's blog, togoforth.org.

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

Oct. 4, 1965, about a year and a half before promulgating his social encyclical "Populorum Progressio," Blessed Paul VI addressed the United Nations on its 20th anniversary. His speech highlighted themes that would later appear in his encyclical.

The U.N., Blessed Paul said, is accomplishing a great work: "teaching men peace." Peace "is not built merely by means of politics and a balance of power and interests" but "is built with the mind, with ideas, with the works of peace," the pope continued.

Blessed Paul named disarmament as one pathway toward peace: "If you want to be brothers, let the arms fall from your hands."

The pope also reminded the U.N. that "the edifice you are building does not rest on purely material and terrestrial foundations" but "upon consciences." In an age "marked by such great human progress," he said, "the appeal to the moral conscience of man has never before been as necessary."

Neither progress itself or science pose direct dangers, but can be used for good, he said. But "the real danger comes from man, who has at his disposal ever more powerful instruments." Modern civilization, concluded Blessed Paul, must be built from spiritual principles.

[[In-content Ad]]